Baroque Treasures, Reconstruction, and Sobering Memories in Dresden

The intriguing and fun city of Dresden, Germany, winds up on far fewer American itineraries than it deserves to. Don’t make that mistake.

Dresden surprises visitors with fanciful Baroque architecture in a delightful-to-stroll cityscape, a dynamic history that mingles tragedy with inspiration, and some of the best museum-going in Germany. A generation ago, Dresden was a dreary East German burg, but today it’s a young and vibrant city, crawling with proud locals, cheery tourists, and happy-go-lucky students who have no memory of communism.At the peak of its power in the 18th century, Dresden, the capital of Saxony, ruled most of present-day Poland and eastern Germany from the banks of the Elbe River. Its king imported artists from all over Europe, peppering his city with fine Baroque buildings and filling his treasury with lavish jewels and artwork. Dresden’s grand architecture and dedication to the arts — along with the gently rolling hills surrounding the city — earned it the nickname “Florence on the Elbe.”

But most people know Dresden for its most tragic chapter: On the night of February 13, 1945 — just months before the end of World War II — Allied warplanes dropped firebombs on the city. Dresden was bombed so hard that a rare firestorm was created — a hellish weather system that ends up sucking much of the city into its fiery center… and oblivion.

Rising above the cityscape is the handbell-shaped dome of the Frauenkirche (Church of our Lady)–the symbol and soul of the city. When completed in 1743, this was Germany’s tallest Protestant church (310 feet high). After the war, the Frauenkirche was left a pile of rubble and turned into a peace monument. Only after reunification was the decision made to rebuild it, completely and painstakingly. It reopened to the public in 2005. Crowning the new church is a shiny bronze cross–a copy of the original and a gift from the British people in 2000, on the 55th anniversary of the bombing. It was crafted by an English coppersmith whose father had dropped bombs on the church that fateful night.

Today Dresden is rebuilt, full of life, and wide-open for visitors. I love strolling Dresden’s delightful promenade. Enjoying its perch overlooking the river, you hardly notice it was once a defensive rampart. In the early 1800s, it was turned into a public park, with a leafy canopy of linden trees, and was given the odd nickname “The Balcony of Europe.” Dresden claims to have the world’s largest and oldest fleet of historic paddleboat steamers. A few of its nine riverboats from the 19th century are ready to take visitors for a ride.

Dresden’s waterfront promenade — the so-called “Balcony of Europe,” seen here from across the river — is a delight.

I find visiting the rebuilt Frauenkirche very poignant. Inside stands the church’s twisted old cross, which fell 300 feet and burned in the rubble. Lost until restorers uncovered it from the pile of stones in 1993, it stands exactly on the place where it was found — still relatively intact.

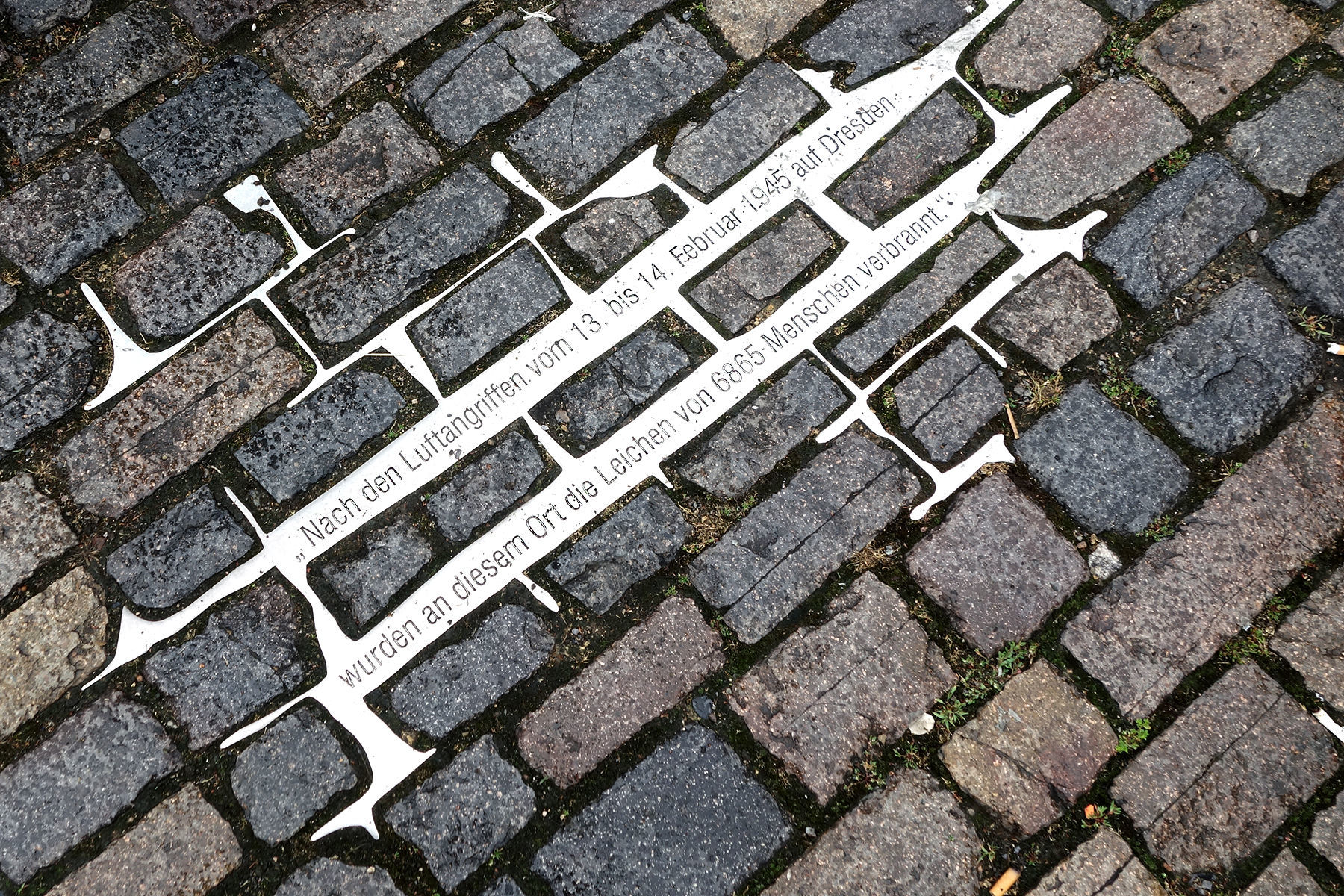

Dresden is a city where the heritage of destruction is hard to ignore. I’ll never forget standing on the Old Market Square… just another square. Then, looking down at the pavement, I saw an inscription that read, “After the air attack on Dresden on February 13-14 1945, the corpses of 6,865 people were burned on this spot.” Carved on a piece of granite above that was a simple statement: “We brought the war to the world, and ultimately it came home to us.”

Dresden’s Inspiring Rebirth

By Rick Steves

Intriguing Dresden, Germany, winds up on far fewer American itineraries

than it deserves to. Don't make that mistake. Since its horrific

firebombing in World War II, the city has transitioned to a thriving

cultural center that's well worth a visit. Even with only a day to

spare, Dresden is a doable side trip from bigger attractions like Berlin

or Prague.

The burg surprises visitors with fanciful Baroque architecture in a delightful-to-stroll cityscape, a history that mingles tragedy with inspiration, and some of Germany's best museum-going. A generation ago, Dresden was dreary, but today it's young and vibrant, crawling with proud locals, cheery tourists, and happy-go-lucky students who have no memory of communism.

Even so, Dresden's heritage of destruction is hard to ignore. I'll never forget standing on the Altmarkt square in the Old Town…it seemed like just another square. Then, looking down at the cobblestones, I saw an inscription that reads, "After the air attack on Dresden on February 13–14 1945, the corpses of 6,865 people were burned on this spot." Carved on a piece of granite above that was a simple statement: "Thus the horrors of war, unleashed by Germany upon the whole world, came back to be visited upon our city."

Four eras have shaped Dresden: its Golden Age in the mid-18th century; the city's devastation in World War II; the communist regime (1945–1989); and the current "reconstruction after reunification" era. Each city sight provides a glimpse into this timeline, so I like to weave my sightseeing into a day-long stroll for the most comprehensive and meaningful visit. The highlights are conveniently clustered along the delightful Elbe River promenade, nicknamed the "Balcony of Europe."

I start at Theaterplatz, the main square and home to the statue of King John of Saxony, a mid-19th century ruler who preserved Saxon culture in Germany. The buildings in this square — like many Dresden landmarks — are reconstructed to resemble their pre-bombing facades. At the head of the square, the sprawling Zwinger palace was once the site of lavish royal celebrations hosted by the Wettin dynasty, which ruled Saxony for eight centuries. Today, this Baroque complex is filled with three museums, including the Old Masters Gallery, featuring works by Raphael, Titian, Rembrandt, and more.

Across the street, the Royal Palace, once destroyed, is being rebuilt — with galleries opening as they're completed. Here, I visit the Historic Green Vault. Wettin dynasty big-shot Augustus the Strong began his Baroque treasury collection here in the early 1700s, and the extravagant trove is clearly designed to wow. The ivory, silver, and gold knickknacks are dazzling examples of Gesamtkunstwerk — a symphony of artistic creations, though obnoxiously gaudy by today's tastes. (It's important to reserve tickets in advance; the number of visitors each day is limited to protect the collection.)

The highlight of my day is a stop at the symbol and soul of the city: the Frauenkirche (Church of our Lady). After World War II, the Frauenkirche was left a pile of rubble and turned into a peace monument. Only after Germany's 1990 reunification was the decision made to rebuild it completely and painstakingly. Over a decade and €100 million later, it reopened in 2005. Inside, the circular nave is bright, welcoming, and poignant, featuring a twisted old cross, which had once been the bright golden cross that topped the whole church, but fell 300 feet and burned in the bombing wreckage. Lost until restorers uncovered it from the debris in 1993, it stands exactly on the place where it was found — still relatively intact. The persistence of this cross symbolizes the themes of the church: rebirth, faith, and resolution.

The Frauenkirche towers over the Neumarkt, a once-central square ringed by rich merchants' homes. The eight quarters that surround the Neumarkt have been rebuilt to resemble the facades of the original structures, and the area is once again alive with bustling cafés. A statue of Martin Luther holding his self-translated Bible reminds passersby of the Reformation that began in nearby Wittenberg.

A short walk toward the water leads me to the end of the Balcony of Europe, where the Albertinum modern art museum boasts a fine collection of work by Gaugin, Monet, Picasso, and Rodin and other Romantic and contemporary masters.

Dresden's intense history and remarkable museums can be draining. To unwind after my walking tour, I head over to the New Town (Neustadt), across the river. The bombs missed most of this area, so it retains its well-worn, prewar character. With virtually no sights, the area is emerging as the city's lively people zone that's best after dark, when the funky Outer New Town sets the tempo for Dresden's trendy nightlife.

Today, Dresden is rebuilt, full of life, and wide-open for visitors. These streets paint a portrait of the city's highest highs and lowest lows. But in this era of cultural rebirth, Dresden is in its prime.

The burg surprises visitors with fanciful Baroque architecture in a delightful-to-stroll cityscape, a history that mingles tragedy with inspiration, and some of Germany's best museum-going. A generation ago, Dresden was dreary, but today it's young and vibrant, crawling with proud locals, cheery tourists, and happy-go-lucky students who have no memory of communism.

Even so, Dresden's heritage of destruction is hard to ignore. I'll never forget standing on the Altmarkt square in the Old Town…it seemed like just another square. Then, looking down at the cobblestones, I saw an inscription that reads, "After the air attack on Dresden on February 13–14 1945, the corpses of 6,865 people were burned on this spot." Carved on a piece of granite above that was a simple statement: "Thus the horrors of war, unleashed by Germany upon the whole world, came back to be visited upon our city."

Four eras have shaped Dresden: its Golden Age in the mid-18th century; the city's devastation in World War II; the communist regime (1945–1989); and the current "reconstruction after reunification" era. Each city sight provides a glimpse into this timeline, so I like to weave my sightseeing into a day-long stroll for the most comprehensive and meaningful visit. The highlights are conveniently clustered along the delightful Elbe River promenade, nicknamed the "Balcony of Europe."

I start at Theaterplatz, the main square and home to the statue of King John of Saxony, a mid-19th century ruler who preserved Saxon culture in Germany. The buildings in this square — like many Dresden landmarks — are reconstructed to resemble their pre-bombing facades. At the head of the square, the sprawling Zwinger palace was once the site of lavish royal celebrations hosted by the Wettin dynasty, which ruled Saxony for eight centuries. Today, this Baroque complex is filled with three museums, including the Old Masters Gallery, featuring works by Raphael, Titian, Rembrandt, and more.

Across the street, the Royal Palace, once destroyed, is being rebuilt — with galleries opening as they're completed. Here, I visit the Historic Green Vault. Wettin dynasty big-shot Augustus the Strong began his Baroque treasury collection here in the early 1700s, and the extravagant trove is clearly designed to wow. The ivory, silver, and gold knickknacks are dazzling examples of Gesamtkunstwerk — a symphony of artistic creations, though obnoxiously gaudy by today's tastes. (It's important to reserve tickets in advance; the number of visitors each day is limited to protect the collection.)

The highlight of my day is a stop at the symbol and soul of the city: the Frauenkirche (Church of our Lady). After World War II, the Frauenkirche was left a pile of rubble and turned into a peace monument. Only after Germany's 1990 reunification was the decision made to rebuild it completely and painstakingly. Over a decade and €100 million later, it reopened in 2005. Inside, the circular nave is bright, welcoming, and poignant, featuring a twisted old cross, which had once been the bright golden cross that topped the whole church, but fell 300 feet and burned in the bombing wreckage. Lost until restorers uncovered it from the debris in 1993, it stands exactly on the place where it was found — still relatively intact. The persistence of this cross symbolizes the themes of the church: rebirth, faith, and resolution.

The Frauenkirche towers over the Neumarkt, a once-central square ringed by rich merchants' homes. The eight quarters that surround the Neumarkt have been rebuilt to resemble the facades of the original structures, and the area is once again alive with bustling cafés. A statue of Martin Luther holding his self-translated Bible reminds passersby of the Reformation that began in nearby Wittenberg.

A short walk toward the water leads me to the end of the Balcony of Europe, where the Albertinum modern art museum boasts a fine collection of work by Gaugin, Monet, Picasso, and Rodin and other Romantic and contemporary masters.

Dresden's intense history and remarkable museums can be draining. To unwind after my walking tour, I head over to the New Town (Neustadt), across the river. The bombs missed most of this area, so it retains its well-worn, prewar character. With virtually no sights, the area is emerging as the city's lively people zone that's best after dark, when the funky Outer New Town sets the tempo for Dresden's trendy nightlife.

Today, Dresden is rebuilt, full of life, and wide-open for visitors. These streets paint a portrait of the city's highest highs and lowest lows. But in this era of cultural rebirth, Dresden is in its prime.

---{-=@

HICKOK