The story of Lafayette Lofts

By Marilyn Cappellino

Special to The News

on December 5, 2015 -

Lou Marconi An overhead of~~~The West Side of Buffalo NY.

Leana Elam Way too cool. I see the treeline etched out in a V then going down the shot it turns into a y. V for Victory and Y for Yes for the Great West Side of Buffalo!!

Lou Marconi The orangeish roof standing out in the left-of-center of the picture is the Presbyterian Church that has now been converted to the LAFAYETTE LOFTS, on the corner of Richmond & Elmwood Avenues. Moving further 'up' on the photo. is Colonial Circle where the Colonel Bidwell Pkwy Statue is. If you can magnify the photo to 300. you can discern the roofing portion of Lafayette High School. Public School # 56 is the dark red building almost literally in the middle of this image.

John L Lochbaum THANKS LOU FOR THE BIRDS EYE VIEW...

Alice DeForest That's great

Linda Pane wow amazing! wink emoticon

Leana Elam Way too cool. I see the treeline etched out in a V then going down the shot it turns into a y. V for Victory and Y for Yes for the Great West Side of Buffalo!!

Lou Marconi The orangeish roof standing out in the left-of-center of the picture is the Presbyterian Church that has now been converted to the LAFAYETTE LOFTS, on the corner of Richmond & Elmwood Avenues. Moving further 'up' on the photo. is Colonial Circle where the Colonel Bidwell Pkwy Statue is. If you can magnify the photo to 300. you can discern the roofing portion of Lafayette High School. Public School # 56 is the dark red building almost literally in the middle of this image.

John L Lochbaum THANKS LOU FOR THE BIRDS EYE VIEW...

Alice DeForest That's great

Linda Pane wow amazing! wink emoticon

Lou Marconi I was employed there on a part-time-basis in 'the-kitchen'; 1968, 1969.

Lou Marconi A very long long long time ago, I TRIED to play youth league basketball---in this very gymnasium; a very very long time ago.

Lou Marconi Architects, we assume, perform a singular function. We think of them as those charged with designing a building structurally sound and aesthetically appealing. Sometimes, though, good architectural firms find themselves engaged in a far broader array of activities like finance procurement, tax law consultation, community relations, in fact, all that is involved in the development or redevelopment of significant buildings. Such was the case with architects Carmina Wood Morris, DPC and Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian Church, a highly valued historic reuse project both exceptionally complex and highly important to the Elmwood Village community.

When the elite Preservation League of New York State gave Carmina Wood Morris its third Excellence in Historic Preservation Award of the night, heads turned. Many downstate heavy-hitters attended the annual ceremony held last May at the New York Yacht Club. Most were surprised that a relatively small Buffalo firm took the bulk of the evening’s awards.

“It was actually a bit embarrassing,” said principle Steven J. Carmina, AIA, who was caught off guard by the attention. “Here I was sitting at the table, feeling humbled by the company we were in, and we turn out to be the night’s big winner.”

“It was actually a bit embarrassing,” said principle Steven J. Carmina, AIA, who was caught off guard by the attention. “Here I was sitting at the table, feeling humbled by the company we were in, and we turn out to be the night’s big winner.”

Still, when he speaks of Lafayette Lofts, his most recent project honored at the New York City ceremony, you get the sense that the award was deserved for effort if nothing else.

Clearly, though, it was given for much, much more. Sitting in CWM’s unfinished conference room on downtown’s ripped-apart 400 block of Main Street, Carmina and lead architect Wendy J. Ferrie, R.A., were asked: “What degree of involvement did your firm have in Lafayette Lofts?” Without hesitation, Carmina said, “150 percent,” adding, “It became for us a bit of a labor of love.” Ferrie wholeheartedly agreed.

Clearly, though, it was given for much, much more. Sitting in CWM’s unfinished conference room on downtown’s ripped-apart 400 block of Main Street, Carmina and lead architect Wendy J. Ferrie, R.A., were asked: “What degree of involvement did your firm have in Lafayette Lofts?” Without hesitation, Carmina said, “150 percent,” adding, “It became for us a bit of a labor of love.” Ferrie wholeheartedly agreed.

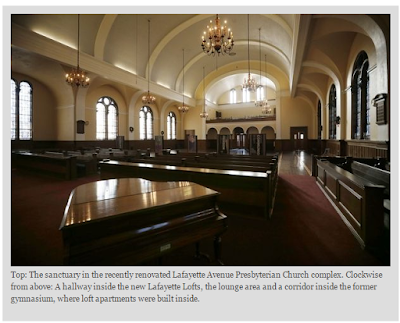

Lafayette Lofts results from an $8.5 million repurpose of the 119-year-old Lafayette Avenue Presbyterian Church and its adjacent Community House located in Buffalo’s historic Elmwood Village. The church, like many, had fallen upon hard times. Once the home of a 1,200-member congregation, it had dwindled to 120 members. The smaller congregation could not continue to support the 60,000-square-foot campus, yet its services and presence were central to the surrounding community.

No one wanted to give up the church; yet no related entity could support it as it was. A decision was made to radically reduce the size of its worship space, and to restructure the complex into a for-profit mixed-use building with 21 market-rate apartments, a prekindergarten school, an incubator kitchen, meeting rooms and several event spaces.

It’s not surprising a structure so old, so large and so intricately designed would be difficult to reshape. But Project Manager Murray Gould, principle of Port City Preservation and a 30-year industry veteran, explained the problems that plagued them went well beyond the norm.

“Nothing about this project was easy,” Gould said while gently shaking his head, eyes cast downward, looking still mildly stunned by his own recollections. “Every step of the way was a struggle.”

Things improved when CWM came on board, but then difficulties with the age and nature of the building began to emerge.

“Nothing about this project was easy,” Gould said while gently shaking his head, eyes cast downward, looking still mildly stunned by his own recollections. “Every step of the way was a struggle.”

Things improved when CWM came on board, but then difficulties with the age and nature of the building began to emerge.

Carmina spoke candidly about his team’s challenges. In his good-natured manner, he listed a few: “We had a building that was not documented very well; we didn’t know what kind of structure they used; we didn’t know what was a bearing wall; we didn’t know which way floor joists ran.” He chuckled. “Plus we had a building that was deteriorating. Windows were deteriorating. Connections between buildings were hard to locate.” With hand pressed to forehead, and a bit of a laugh, he continued, “And then there was financing. The project was, I think, the first of its kind in Western New York where you have an operating not-for-profit [a church] developing a for-profit entity [LAPC Lofts] so that tax credits could be bought. That whole maneuver with setting up corporations, profit versus not-for-profit, protecting the singularity of the church and so on, all that was very interesting, and technical and had a lot of moving parts, and we were involved in all of it.”

The biggest obstacle the team faced was presented by the National Parks Service.

The biggest obstacle the team faced was presented by the National Parks Service.

The Parks Service rejected the church’s first application for historic preservation tax credits – a rejection that threatened to fold the project.

“Without those tax incentives,” Gould said, “the project was simply not financially viable.”

Armed with new plans, new drawings and a very persuasive presentation designed to reverse the powerful committee’s decision, Carmina and Gould went to Washington, D.C., to make a case to the Parks Service.

The original plans called for removing a stage within the building’s auditorium, and then using that space for residential units. The National Parks Service didn’t like that idea. It wants public spaces to show what was in place when landmark structures were first built. To the Parks Service, the corridors edging the apartments were public space, thus the stage had to remain visible to any person walking the corridors. But preserving the stage would have eliminated much-needed rental units.

CWM found a workable alternative. It proposed that rather than save the full stage, it would instead preserve just the stage frame known as the proscenium arch. Reasoning that the frame was what was visible from the public corridors, the new plan was to build a wall within the original proscenium that resembled a stage curtain, and then build apartments that would sit behind the wall. The plan worked. Tax credits were subsequently awarded, allowing the project to regain its momentum.

“Without those tax incentives,” Gould said, “the project was simply not financially viable.”

Armed with new plans, new drawings and a very persuasive presentation designed to reverse the powerful committee’s decision, Carmina and Gould went to Washington, D.C., to make a case to the Parks Service.

The original plans called for removing a stage within the building’s auditorium, and then using that space for residential units. The National Parks Service didn’t like that idea. It wants public spaces to show what was in place when landmark structures were first built. To the Parks Service, the corridors edging the apartments were public space, thus the stage had to remain visible to any person walking the corridors. But preserving the stage would have eliminated much-needed rental units.

CWM found a workable alternative. It proposed that rather than save the full stage, it would instead preserve just the stage frame known as the proscenium arch. Reasoning that the frame was what was visible from the public corridors, the new plan was to build a wall within the original proscenium that resembled a stage curtain, and then build apartments that would sit behind the wall. The plan worked. Tax credits were subsequently awarded, allowing the project to regain its momentum.

Lou Marconi Ferrie, who supervised the project, spoke about complexities in designing infrastructure.

“Usually, you have one, maybe two sets of [building] code to follow,” she said. “Here we had the school, apartments, commercial kitchen, banquet halls, all with differing code. Plus we had the restrictions that come with historic preservation, like not running laundry room vents outdoors, or assuring that modern piping isn’t seen in public spaces.”

Those challenges alone kept Ferrie busy. For a period of two years, she spent four hours a day at the site.

“We didn’t have an engineer predesign. Instead, I was there walking with the guys trying to figure out how we can make a bathroom work, electrical work, where we can run things.”

Ferrie noted that although tough, the job was also filled with fun and some big discoveries.

A major find was the spectacular Summer Chapel, a richly ornate space hidden for more than half a century behind 1950s drywall and dropped ceilings.

“Usually, you have one, maybe two sets of [building] code to follow,” she said. “Here we had the school, apartments, commercial kitchen, banquet halls, all with differing code. Plus we had the restrictions that come with historic preservation, like not running laundry room vents outdoors, or assuring that modern piping isn’t seen in public spaces.”

Those challenges alone kept Ferrie busy. For a period of two years, she spent four hours a day at the site.

“We didn’t have an engineer predesign. Instead, I was there walking with the guys trying to figure out how we can make a bathroom work, electrical work, where we can run things.”

Ferrie noted that although tough, the job was also filled with fun and some big discoveries.

A major find was the spectacular Summer Chapel, a richly ornate space hidden for more than half a century behind 1950s drywall and dropped ceilings.

Lou Marconi “We didn’t know the chapel existed,” Ferrie said. “Then one day, in the space that was being used as the church’s pre-K, Murray [Gould] finds a tiny little door that led up to a rickety little staircase, and there we found the trusses.”

The huge trusses, along with giant coved ceilings and Gothic arched windows, brought the team back to the drawing board. The chapel ended up converted into four apartments, each multilevel townhouse style, and all with exceptional architectural features. A couple have generous portions of the trusses dressing 22-foot ceilings; a row of architectural windows appears in another; a former choir loft became a sunken living room with a ceiling that peaks at 28 feet.

Those apartments made from space accidentally found became the only residential units located within the main church building, and are now among Buffalo’s most unique and historically significant apartments.

Another of Ferrie’s jobs was finding aesthetic purpose to quirky architectural elements scattered throughout the complex. Among them were two old bowling alleys running through space intended to be a ground-floor apartment. Rather than cover them, Ferrie, along with her design team, decided to use the alleys as artistic flooring elements, leaving them fully exposed, pin-stops and all.

The huge trusses, along with giant coved ceilings and Gothic arched windows, brought the team back to the drawing board. The chapel ended up converted into four apartments, each multilevel townhouse style, and all with exceptional architectural features. A couple have generous portions of the trusses dressing 22-foot ceilings; a row of architectural windows appears in another; a former choir loft became a sunken living room with a ceiling that peaks at 28 feet.

Those apartments made from space accidentally found became the only residential units located within the main church building, and are now among Buffalo’s most unique and historically significant apartments.

Another of Ferrie’s jobs was finding aesthetic purpose to quirky architectural elements scattered throughout the complex. Among them were two old bowling alleys running through space intended to be a ground-floor apartment. Rather than cover them, Ferrie, along with her design team, decided to use the alleys as artistic flooring elements, leaving them fully exposed, pin-stops and all.

Lou Marconi In another apartment, CWM left an iron antique safe about the size of a bedroom dresser in the corner of a living room. Like the bowling alleys, the safe is now a fun conversation starter. Even light cages, used in the former gymnasium to protect bulbs from flying basketballs, were kept in place, creating uniquely attractive lighting fixtures.

Through much of her time at Lafayette Lofts, Ferrie was expecting twins; then she was adjusting to motherhood.

“When we did the final tour, I brought my kids with me, which was really weird because they didn’t exist when we started this project.”

Watching her 2-year-olds run up and down a small staircase that leads to nowhere (another of her preserved artifacts), Ferrie marveled at all that had evolved since CWM began work on Lafayette Lofts.

The other 2015 preservation awards given to CWM were for 10 Lafayette in downtown Buffalo, and Remington Lofts, located across from the Erie Canal in North Tonawanda. The firm twice before received the award. First in 2008 for Webb Lofts, and again in 2013 for Hotel @ the Lafayette, both in downtown Buffalo.

Marilyn Cappellino is a freelance writer from East Amherst.

Through much of her time at Lafayette Lofts, Ferrie was expecting twins; then she was adjusting to motherhood.

“When we did the final tour, I brought my kids with me, which was really weird because they didn’t exist when we started this project.”

Watching her 2-year-olds run up and down a small staircase that leads to nowhere (another of her preserved artifacts), Ferrie marveled at all that had evolved since CWM began work on Lafayette Lofts.

The other 2015 preservation awards given to CWM were for 10 Lafayette in downtown Buffalo, and Remington Lofts, located across from the Erie Canal in North Tonawanda. The firm twice before received the award. First in 2008 for Webb Lofts, and again in 2013 for Hotel @ the Lafayette, both in downtown Buffalo.

Marilyn Cappellino is a freelance writer from East Amherst.

---{-=@

Hickok

No comments:

Post a Comment